KV 5

KV5 is more than just a tomb. Okay, sure it’s a subterranean, rock-cut tomb in the Valley of the Kings, that belonged to the sons of Ramesses II. But it’s also one of the biggest discoveries since King Tut’s tomb in 1922.

Think of KV5 as more than just a tomb, it’s more like a family mausoleum for Rameses II. This thing is huge, with 121 corridors and chambers.

Though KV5 was partially excavated as early as 1825, its true extent was discovered in 1995 by Kent R. Weeks and his exploration team. The tomb is now known to be the largest in the Valley of the Kings. Weeks’ discovery is widely considered the most dramatic in the valley since the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun in 1922.

The entrance to KV 5 was still visible in the nineteenth century, however. The first one to probe inside was James Burton, an Englishman who visited the Valley in 1825. He noted the name of Rameses II carved in the entrance. Burton’s workmen dug a channel through the first three debris-filled chambers, but he saw no objects or wall decorations and abandoned the work.

Howard Carter uncovered the doorway in 1902, and then immediately re-buried it, thinking the tomb was small, undecorated, and of no importance. KV 5’s exact location was forgotten. It was not until 1987 that the entrance was seen again when it was re-located by the Theban Mapping Project. The TMP had been working at the mouth of the Valley of the Kings because of a government decision to widen the roadway here. It knew from Burton’s records that KV 5 lay in this area, and was concerned that it might be damaged by the proposed engineering work. No one knew at the time of KV 5’s real importance.

The road into the Valley narrowed at this point, just before the tomb of Rameses IX (KV 6). It was a strategic location for souvenir vendors to hawk their wares to tourists. It took only ten days of digging to uncover the entrance to KV 5 in the hillside behind the kiosks.

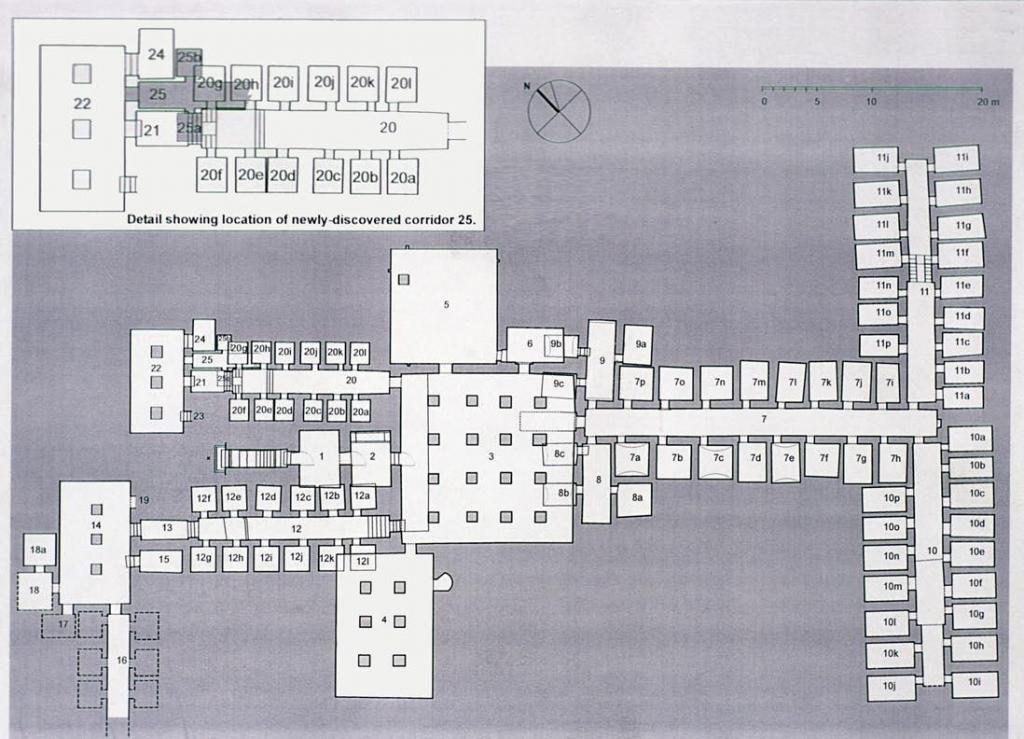

The Theban Mapping Project’s excavations have shown that KV 5 contains not just the six rooms first seen by Burton in 1825, but over 110 corridors and chambers dug deep into the hillside. It is, in fact, one of the largest tombs ever found in Egypt. From the wall reliefs and objects found on the floors, we now know that KV 5 was the burial place of the sons of Rameses II. The tomb is unique in size, in plan, and in purpose. Many have called the work in KV 5 one of the most exciting and important archaeological projects of the twentieth century.

In 1990, the TMP built walls around the entrance of KV 5 to protect against flooding. The kiosks were moved by order of the government, and all vehicular traffic was banned. On the right was a power transformer, finally removed in 1997. On the left was our “field office,” replaced by a canvas tent and caravan trailer.

Chronological overview of discoveries in KV 5

1825

Burton dug channels through the first three chambers. He was also able to crawl into three other chambers, probing with a stick into inaccessible corners to determine their rough dimensions.

1987-1994

Between 1987 and 1994, the TMP began clearing the first two chambers of KV 5. It did not know yet that the tomb might extend beyond the rooms Burton sketched in his notebook. TMP staff, however, saw extensively painted reliefs on the walls and found thousands of objects on the floors. These included inscriptions giving the names of several of the sons of Rameses II, proof that KV 5 was a family mausoleum.

1995

Unable to remove the debris from the structurally unstable sixteen-pillared chamber 3, in 1995 the TMP turned its attention to gate 7 in the rear wall of the chamber. Once through the gate, clogged to the ceiling with debris, the level of the fill dropped. It was possible to crawl forward into a long, T-shaped set of corridors that had not been entered in over three thousand years. KV 5, once thought to be unimportant and undecorated, was now known to contain over sixty-seven chambers with traces of paint and reliefs, making it the largest tomb ever found in the Valley of the Kings.

1996

Returning to pillared chamber 3, the TMP found two gates. These apparently led to parallel corridors 12 and 20 sloping downward beneath the road and towards KV 7, the tomb of Rameses II.

1997

As of spring 1997, one of the two parallel corridors (12) had been partially explored. It leads to a three-pillared chamber (14) from which yet another corridor (with more side-chambers) runs into the heart of the Valley of the Kings. Over 110 chambers were now known, and KV 5 had become one of the largest tombs ever found in all Egypt.

KV 5 is located in the main wadi of the Valley of the Kings. The tomb may originally have been a Dynasty 18 tomb (consisting of chambers 1, 2, and part of 3) usurped by Rameses II as the burial place for several of his principal sons. Still, under excavation, the tomb has so far revealed 121 corridors and chambers. Since the tomb appears to have several bilaterally symmetrical sections, it is likely that the number of chambers will increase to 150 or more in subsequent field seasons. KV 5 itself is the largest tomb in the Valley; pillared chamber 3 is the largest chamber of any tomb in the Valley of the Kings.

At least six royal sons are known to have been interred in KV 5. Since there are more than twenty representations of sons carved on its walls, there may have been that many sons interred in the tomb.

The tomb is decorated with scenes from the Opening of the Mouth ritual (pillared chamber 3) and representations of the king, princes, and deities (chamber 1, chamber 2, gate 3, pillared chamber 3, corridor 7, chamber 8, gate 9, corridor 12).

- Structure: KV 5

- Location: Valley of the Kings, East Valley, Thebes West Bank, Thebes

- Owner: Sons of Rameses II

- Other designations: 5 [Lepsius], 8 [Hay], Commencement d’excavation ou grotte bouchée [Description], M [Burton]

- Site type: Tomb

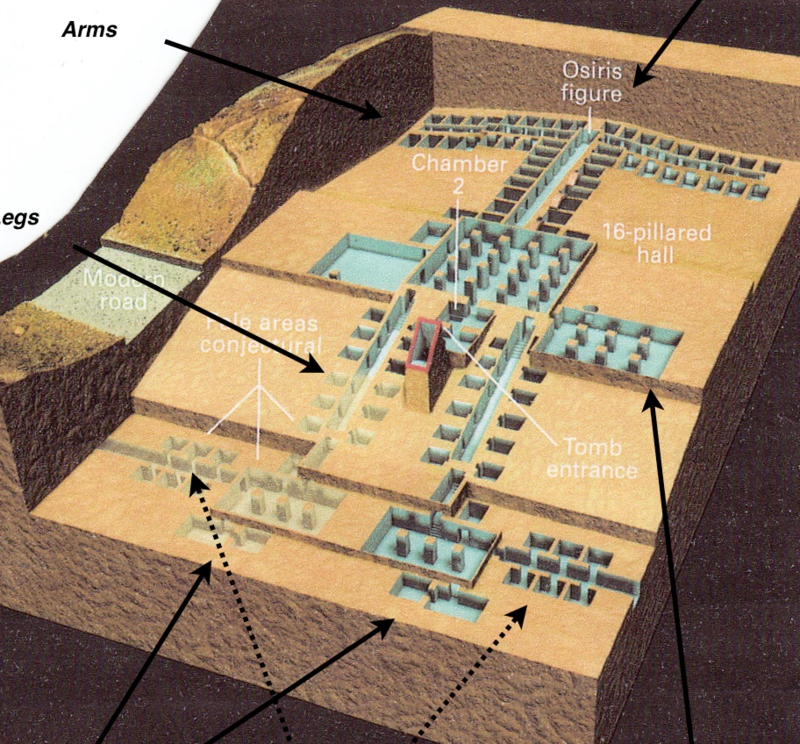

Noteworthy features: The overall plan of this tomb is unusual: there is a change in the tomb’s principal axis after chamber 3; several chambers lie beneath other chambers; two corridors extend toward the northwest beneath the entrance and the road in front of the tomb; the plan is unlike any other royal tomb. Pillared chamber 3 has more pillars (sixteen) than any other chamber in the Valley of the Kings. The sculpted Osiris figure in the recess at the end of corridor 7 is unique.

- Axis in degrees: 134.18

- Axis orientation: Southeast

Site Location

- Latitude: 25.44 N

- Longitude: 32.36 E

- Elevation: 169.87 msl

- North: 99,637.895

- East: 94,095.771

- Modern governorate: Qena (Qina)

- Ancient nome: 4th Upper Egypt

Measurements

- Maximum height: 2.85 m

- Mininum width: 0.61 m

- Maximum width: 15.43 m

- Total length: 443.2 m

- Total area: 1266.47 m²

- Total volume: 2154.82 m³

Additional Tomb Information

- Entrance location: Valley floor

- Owner type: Prince

- Entrance type: Staircase

- Interior layout: Corridors and chambers

- Axis type: Straight

Decoration

- Grafitti

- Painting

- Raised relief

Categories of Objects Recovered

- Human remains

- Jewelry

- Mammal remains

- Religious objects

- Tomb equipment

- Transport

- Vessels

- Written documents

Site History

A small tomb perhaps dating to Dynasty 18 was appropriated by Rameses II and considerably enlarged in several phases. There is no evidence of re-use of KV 5 after the reign of Rameses II. The tomb was first visited in modern times by James Burton, who mapped its first nine chambers. Its greater extent was realized by the Theban Mapping Project in 1995, and more chambers continue to be discovered until today.

This site was used during the following period(s):

- New Kingdom, Dynasty 18 (entryway A, chambers 1 and 2, and part of pillared chamber 3)

- New Kingdom, Dynasty 19, Rameses II

Conservation history: The tomb is currently undergoing engineering and conservation work as it continues to be cleared.

Site condition: The tomb was robbed in antiquity. Since then, it has been hit by at least eleven flash floods caused by heavy rains in the Valley. These have completely filled the tomb with debris and seriously damaged its comprehensively decorated walls. From about 1960 to 1990, tour buses parked above the tomb; their vibrations caused serious damage to parts of the tomb near the roadway, as did a leaking sewer line installed over the entrance when the Valley of the Kings rest house was built.